SenseIT

4/2/2022

Digital Accessibility Standards, Then and Now

In our last post in this series, we covered the beginning of mandated accessibility standards in U.S. law. The focus was on infrastructural accessibility, since that was the relevant domain at the time the laws were passed, but the computer revolution was just around the corner.

Digital accessibility was a natural offshoot of infrastructural accessibility, and it came about shortly after advances in digital technology proved that it was here to stay. Today, digital accessibility is a field unto itself, and as more and more of our lives move online, it’s only becoming more important.

The ADA’s Expansion of Title III

In 1996, the Department of Justice decided that Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (which, if you don’t remember from our last post, is about public accommodations and public services rendered by private entities) did in fact apply to digital content. Websites were now considered public accommodations, and so had to be accessible to people with disabilities. This decision would be the first to jumpstart the concept of digital accessibility as a legislative issue.

It's worth noting that in 2008, the ADA Amendments Act (ADAAA) broadened the definition of “disability,” meaning that people who had partial sight, other partial physical disabilities, or minor cognitive disabilities were now protected under the ADA as well. This means that digital content needed to take these into account in addition to the more straightforward disabilities already covered by the law.

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines

In 1999, the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), founded by the “official” inventor of the internet, Tim Berners-Lee, came out with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG 1.0). These guidelines gave practical meaning to the legislation passed three years prior, but since they weren’t reinforced by any legal requirement, it was up to individual organizations to adopt them.

Nine years later, in 2008, the W3C published WCAG 2.0, which built upon the foundation set in WCAG 1.0, but took the significant advances that had occurred in the technology over the last nine years into account.

And in 2018, the W3C published WCAG 2.1[i]. This is an extension of version 2.0, and if a website complies with 2.1, it de facto complies with 2.0. The WCAG 3.0 is currently in development, and it is on track to be finalized in the next few years[ii].

The Rehabilitation Act – Section 508

In 1986, The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 was amended to include Section 508[iii], and in 1998, Section 508 was amended to include digital content. Section 508 covers Federal Electronic and Information Technology – meaning that if any federal agency develops, procures, maintains, or uses electronic and information technology, they must ensure that it is accessible to employees and members of the public with disabilities. It includes computers, software, and electronic office equipment, and focuses largely on federally maintained websites.

The Access Board (created in Section 502) is responsible for developing the accessibility standards, which must be adhered to unless doing so would place an “undue burden” on the Federal agency in question (in which case, the agency has to provide an acceptable alternative under the law).

In 2017, the Access Board refreshed Section 508 with new guidelines for Information and Communication Technology (ICT) accessibility[iv]. The guidelines importantly included a section that requires broad application of the WCAG 2.0 guidelines (this was a year before version 2.1 was published, and the law has not been updated to reflect that). This would mean that any ICT that was covered by the law had to adhere to the WCAG 2.0 standards, which included smartphones as well as desktop platforms. It also meant that there would be more consistency across multinational platforms than there had been, since the WCAG 2.0 was the most comprehensive accessibility standard at the time and other countries were also beginning to develop digital accessibility policies.

Upholding the Standards

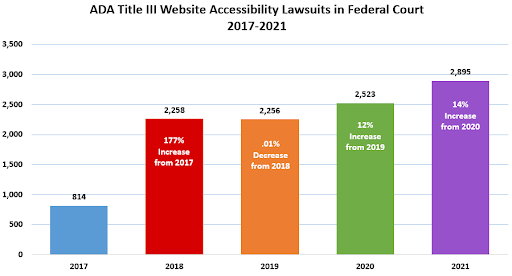

Unlike the development of a building, you don’t need a permit to develop a digital product. Therefore, monitoring whether or not a given product complies with accessibility standards is usually done after the fact and is enforced via private lawsuits. Hopefully this approach will change, since it’s both inefficient and places an unfair burden on both sides of the judge’s bench (we at SenseIT have some ideas about that). But in the meantime, ADA Title III website accessibility lawsuits are increasing rapidly and consistently[v]. And with the Coronavirus pandemic spurring more businesses to offer online services than ever before, we can assume that these lawsuits will continue unless we can make the internet a more universally accessible space.

Digital technology continues to advance exponentially, and in ways that are difficult for most of us to predict. Digital accessibility standards will need to match that pace, and the best way to do it is to take accessibility into account while developing new digital products and updating old ones. In this series we’ve covered theories of disability, the adoption of infrastructural accessibility standards as a social movement, and now the digital accessibility standards we know and love. These standards are more than just rules to follow or face legal redress – they are useful guidelines to help all of us create a more inclusive digital world.

[i] You can read more about it here.

[ii] Source: https://www.w3.org/WAI/standards-guidelines/wcag/wcag3-intro/

[iii] Source: https://www.access-board.gov/law/ra.html

[iv] Source: https://www.regulations.gov/document/ATBCB-2015-0002-0144

[v] Read more here: https://www.adatitleiii.com/2022/03/federal-website-accessibility-lawsuits-increased-in-2021-despite-mid-year-pandemic-lull/

This may also interest you

SenseIT

Digital Accessibility and Improving Your ESG Score

10/4/2022

SenseIT

Universal Design – Approaching Accessibility as A Universal Issue

11/13/2022

SenseIT

Becoming a Unicorn – An Accessible Product Sets You Up For Success

6/16/2022